Alumna Profile: Anahid Simitian

Along with her partner, the architect has a vision for urban, inclusive spaces.

Even before joining LAU, Anahid Simitian (BArch ’13) had always found herself connected to the university in one way or another. As a high schooler, she had signed up for the LAU Global Classrooms Model United Nations (GCMUN) simulation program, and often joined her mother, Salpi Simitian (BA ’08) on campus.

While LAU was a natural decision for her bachelor’s degree, deciding on architecture as a major and a future career required research and thorough introspection. Simitian’s career spans an MS in Advanced Architectural Design at Columbia University and co-founding an architecture and urban design firm that operates between São Paulo and Beirut. In between, she came back to her alma mater to teach Design Studio and Theory of Architecture at the School of Architecture and Design.

In this joint interview, Simitian and her husband and business partner Bruno Nakaguma Gondo touch on the challenges of the industry, their career plans and architecture in Lebanon.

What made you pursue architecture in the end, given your interest in diplomacy?

AS: My passion for MUN was driven by the desire to mediate and establish peaceful interaction among people of diverse backgrounds. That experience helped me realize that the process at the UN had inherent obstacles that were difficult to cut through. Architecture is both a medium of representation and a tool to produce spaces that provide a platform for productive encounters. The obstacles and conflicts can be dealt with through designing and constructing inclusive spaces.

Tell us about your firm, Oficina Aberta. How did you start it and what sets it apart?

AS: We founded the firm in 2016, right after we graduated from Columbia. Our projects are driven by research: revisiting architectural theory texts, on-ground conversations with locals, and translating their needs into spaces that improve everyday life. While Bruno is focused on future innovations and finding solutions for imminent challenges, I like learning from history – so our interests complement each other. The lessons learned from different architectural movements and typologies, coupled with the fascination with technological innovations in design and construction, engender a holistic approach to architecture.

BNG: We tackle every project with multidisciplinary research. We often spend time explaining to clients the path to producing the design – through research and rationale – rather than presenting the design on its own.

What type of projects does your firm take on now?

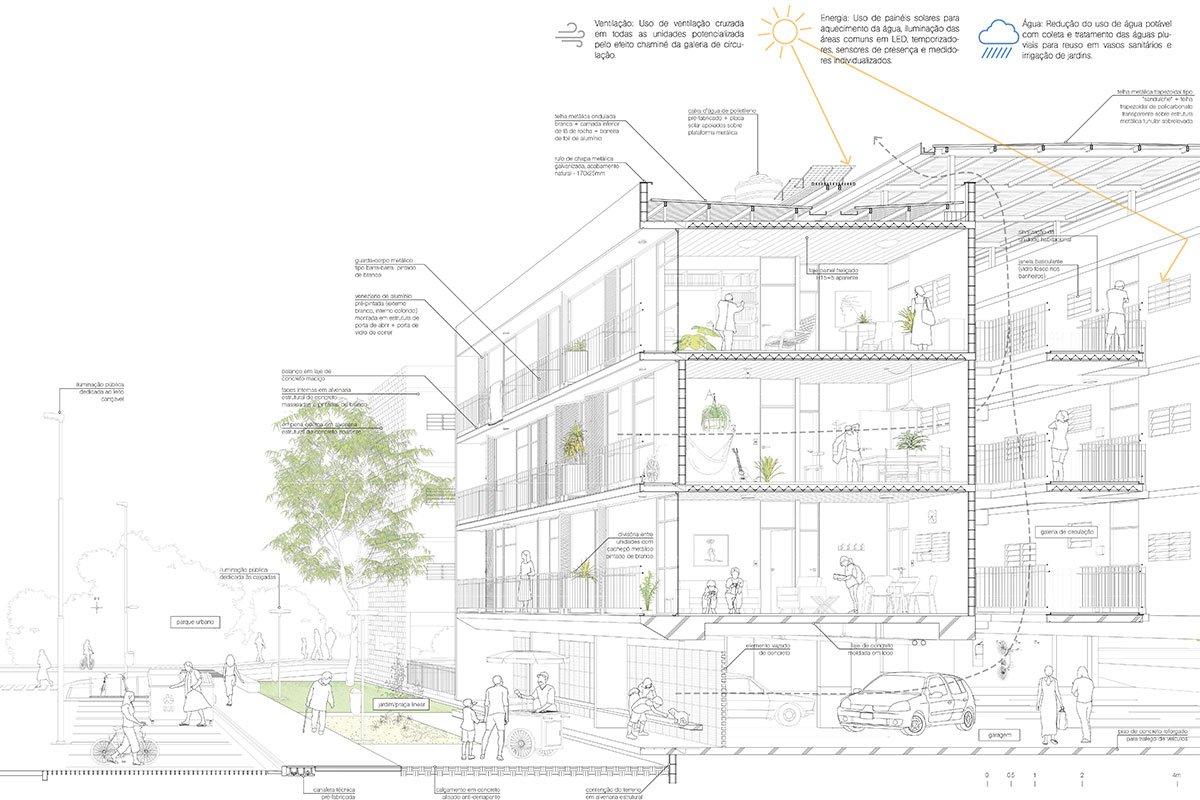

AS: We enjoy working on projects in the public sphere including educational institutions and housing projects. In 2018, we won first place in a competition to design and execute the UFJF Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism in Minas Gerais, Brazil – our first large-scale commission. While we currently have clients from the private sector, we are always on the look-out to pitch to governmental, large-scale projects. Actually, one of the reasons we are in Lebanon is to take part in the KIC Competition at the Rachid Karame International Fair in Tripoli.

BNG: Back in São Paulo, we are currently taking on projects to build social housing, which are commissioned by the private sector, using federal funding. In 2017, we designed and constructed Escola Catavento. Originally, they wanted an extension to accommodate the kindergarten, but we suggested an independent structure surrounded with an open-air play area. The children now enjoy the outdoors and have a closer relationship with nature.

What is your take on the architecture scene in Lebanon?

AS: Compared to the architecture in Brazil, where modernist architecture has been transformed to be an integral part of national identity, what Lebanon may lack is a collective vision of the built environment, that should be reflected specifically in the design and execution of public institutional buildings. The Centro Cultural São Paulo is an example of how a metro station doubles as a cultural center. Well-functioning public transportation inherently brings people from different backgrounds together in a culturally engaging space, and we have yet to see this in Lebanon.

BNG: Some of the best architecture firms in the world are currently designing projects in Beirut. While most of them are for the private sector, there are a few noteworthy projects such as the new Beirut Museum of Art (BeMA), which is to be designed by WORKac. This bodes well for good, inclusive design. I believe Beirut is becoming a hub for world-class architectural work.

How was your experience coming back to LAU as a lecturer?

AS: I had a very positive experience combining my practice with academia as they both fed into and inspired one other. When I went to Columbia University for graduate school, I was nervous at first but quickly came to realize how empowered I was with the tools that LAU had given me. Coming back here to teach, I wanted to pass on this confidence to my students – that they are capable of going to any graduate program after having worked hard and made the ultimate use of the network of faculty and resources that LAU offers.