Chaouki Chamoun on the artist’s role

At the age of 65, Dr. Chaouki Chamoun visited the desert for the first time. On a visit to Abu Dhabi, he took an evening trip out into the emirate’s vast, rolling sea of sand dunes, and suddenly everything changed.

Born in 1942 in the fertile Bekaa Valley, Chamoun grew up hearing his father speak of the Arabs’ ancient ties to the desert. Educated in New York and inspired by the great masters of Western art, Chamoun thought of the desert as part of his past. But when he saw it for the first time, it became the key to his future.

“When I slept on the sand there it was like another world – dreamlike,” he says. “I held the sand in my hand and it filtered through my fingers like golden liquid. I looked at the stars above me – in the desert it’s like an overwhelming dome. The desert took me back to childhood dreams… Suddenly the desert became my painting. I was sunk into it.”

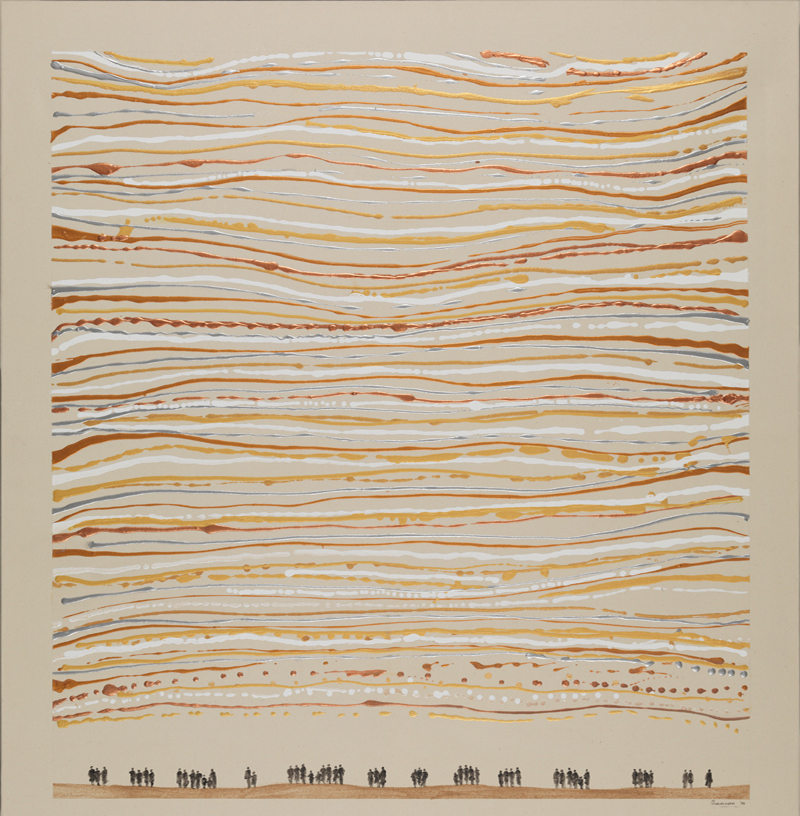

Chamoun’s desert canvasses are rich and varied, capturing the gold and ochre sands in blazing sunlight or lit by thousands of stars. In other paintings, vast skyscrapers sprout from the sand like geometric plants, nourished by oil and the dreams of the ruling sheikhs.

One of Chamoun’s talents as an artist is his capacity for change. His work is unusually diverse, demonstrating a thirst for experimentation. From his series of paintings of waterlilies — contemporary takes on Monet’s immortal subject — to angry, black-dominated abstracts completed during Lebanon’s 2006 War, to vast landscapes and dazzling cityscapes, Chamoun constantly shifts his focus and breaks new ground in his work. Often, his landscapes contain a line of tiny human figures, waiting for new wonders to be revealed.

A long-time fine arts faculty member at the Lebanese American University, the newly-retired painter is also responsible for helping to shape a generation of young Lebanese artists.

“My experience at LAU was really amazing,” he recalls. “I still feel I am a part of it, because I gave this university and the students everything I have. I believe that it’s not only my painting that it’s good to leave behind. What I have learned must also pass to other people.”

The most satisfying part of the job, he says, was watching students grow in confidence and develop their own artistic identity. “We need to see kids growing up with their own style, their own names, so in the 30 years or so I had in higher education I would never let anyone copy my work. I always told me students, ‘If you do not surpass me, and all my generation, it means we have failed to take you to another level.’”

Chamoun had his first solo show in Paris in May, a sort of mini-retrospective at Mark Hachem Gallery, showing work from 2006 to 2015. “It was something I was looking forward to,” he says, “and I was amazed how well it was received, despite the fact it’s my first exhibit there.” A prolific painter, Chamoun was able to include just a fraction of the work he’s produced over the past decade. “I have work sitting in me and it wants to get out,” he explains. “I paint every day.”

He says that the art scene in Lebanon has changed dramatically in the past few decades. “No matter how we look at it we are still under the influence of the West,” he says, “and I can say with pride that my education is really rooted in the Western culture. The East, now, is trying to grow, but they are growing in a way that’s part of the global growth. What’s going on is Paris now is going on in Beirut. People are getting involved in all different kinds of art now, from painting, to sculpture, to illustration, to video art, to installation, to street art… Look at what’s happening in the auction houses. There are bringing values to paintings in the Middle East that they didn’t have 10 or 15 years ago. The excitement, living in those times — I feel lucky to be part of it.”

One question that often preoccupies him is the role of the artist. “Is there a need for me, as an artist, in society? Sometimes I sit and think about this,” he says. “There is a need for scientists. There is a need for medicine. What is the need for a painting to be on the wall, or a sculpture to be in a public place? If I question this, I get closer to myself and to understanding what’s expected of me… I think artists are a refining touch on society. Aesthetics are what we need most as we grow more and more civilized… If I can give enjoyment to people then I must be doing something that society needs.”

One thing is certain. As he steps out of academia, Chamoun will never retire. He will continue painting and his legacy will live on.