The Copy/Paste Syndrome and the Fetish of Originality

It has become something of a fetish in cultural production and consumption. Yet, in the English language at least, “originality” and “authenticity” are slippery terms, as likely to suggest “foundational,” and “traditional” – itself a fetish in the culture of politics and religious belief — as they are “innovative.”

Nowhere has the fetish of originality been more pervasive than in the art market.

As Orson Welles pointed out in his 1973 documentary “F is for Fake,” it takes talent to plagiarise well. In his subject, Elmyr de Hory, Welles offers a profile of a truly great forger. Hory won notoriety not by copying recognised works by the modern masters, but by creating original works in the manner of one master or another. These he passed off to agents and gallerists as lost work, newly discovered, and used the proceeds to fund a comfortable life in Ibeza.

Notorious as it is, Hory’s story was replayed in January 2016. A pair of New York confidence artists — Jose Carlos Bergantiños Diaz and Glafira Rosales — faced trial for having talked otherwise reputable galleries and collectors into spending millions of dollars on fake works ascribed to masters like Rothko and Pollock.

The talent behind this con was Pei-Shen Qian, a Chinese artist whom Bergantiños discovered peddling his work on the roadside. He contracted Pei-Shen to copy great works for his friends at $500 a pop. He then “aged” the canvases with tea and dirt and gave them to Rosales to fob off on galleries as the real thing.

Though Rosales was never able to prove the provenance of the fake works, experts accepted their originality, won over by the authenticity of Pei-Shen’s style.

Rosales admitted under oath to moving more than 60 “lost” works by Rothko, Pollock and others to New York art dealers. When Pei-Shen learnt his works were being sold for millions of dollars, he raised his price to $5,000 per canvases. Bergantiños and Glafira reportedly made $30 million from the scam.

Nuqat (dots) is a Kuwait-based non-profit founded and helmed by self-declared “cultural visionaries” from around the Gulf and Lebanon. Nuqat defines its purpose as one of identifying, tackling, and resolving “creative issues with the aim of gathering and educating an empowered public who go on to enact change in the Middle East.”

Its mission “is to advance creativity and enrich society […] initiating social design projects and connecting innovative powerhouses in the region.”

Since 2009 Nuqat has hosted yearly gatherings concerned with the creative professions — design, advertising, architecture, fashion, production, art. The subject of the non-profit’s most recent conference, in November 2015, was the copy/paste syndrome.

In its brief for “The Copy/Paste Syndrome,” Nuqat promised to examine “how imitation both inspires and limits creative production,” asking, “Is anything original? Is imitation a disease?”

Several LAU faculty members took part in the Nuqat conference.

Yasmine Taan, the chair of LAU’s Department of Design, took advantage of Nuqat to introduce Kuwait to Hilmi Al-Tuni, specifically “Hilmi Al-Tuni: Evoking Popular Arab Culture” (Khatt Foundation, 2014), her illustrated monograph on the Egyptian artist and illustrator, published in Arabic and English-language versions.

With half a century of editorial design under his belt, Tuni is ranked among the Arab world’s most prominent and enduring illustrators and book designers and credited with forming the visual sensibilities of generations of Arab children and adults.

-His work has been premised on the belief that design is the means to bring art to the average person and he strove to develop a distinctly Arab style of illustration, mingling modernist technique with traditional fonts, Islamic and pre-Islamic symbolism and pop culture tropes.

Taan’s book outlines the breadth and variety of Tuni’s oeuvre and discusses the work with the artist himself. Tuni was also present, both for the book launch and to unveil an exhibition of some of his illustrations, curated by Nagla Ismail.

“I’m against copy-pasting, of course,” Taan says, yet she doesn’t see cultural production in bipolar terms — with “original” work at one extreme and “derivative” work at the other. In design she sees an interplay of “originality” and “emulation.”

-“With social networking, and the proliferation of images we see today,” she said, “for me there’s a fine line between influence or emulation and copying.

“At the same time, I think about these international DJs who come to Beirut, basically working with copy-pasted soundtracks. It’s a socially, culturally accepted practice. It’s advertised everywhere. The DJ’s original contribution is the order in which he packages the tunes. It’s a curatorial contribution.

“It makes me think of [Lebanese contemporary artist] Akraam Zaatari’s practice, and specifically his work with [Saida’s veteran studio photographer] Hashem el Madani – the way he places [Madani’s] photos in different contexts, applying another narrative layer or dimension to the work.”

Taan says the copy/paste syndrome casts her mind back to Walter Benjamin’s 1936 essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” which ruminates upon the aesthetic consequences of photography and cinema. Such mechanically reproducible images, he feels, lack the aura of originality or authenticity found in paintings, for instance, while the heavy hand of the photographer makes the work tend toward the totalitarian in a way that pre-mechanical forms are not.

“I remember reading [illustrator and improvisational musician] Mazen Kerbaj’s blog in 2006,” Taan recalled. “He told his readers that, until the end of the war, they could do what they liked with the images he posted online. He never set an end date, but at that point no one knew the Israeli siege would continue for 34 days.”

Taan says having Hilmi Al Tuni with her while presenting his work was fascinating, if stressful.

“I shared the stage with Tuni, an artist in his 80s. I was nervous because I’d never shared my presentation on his work while he’s present – juxtaposing his work with other artists who may have influenced him. I was terrified he’d stand up partway through and say, ‘What are you talking about? I don’t even know this artist!’

“Fortunately he was very gracious. He did wonder about the point of the conference, though. ‘Why are we even talking about this subject? It’s completely wrong, copying someone else’s work!’

“When discussing Tuni’s oeuvre I focus on how useful it is for artists to know what’s come before and how that can enrich our appreciation of his work. One reason Tuni stands up as an artist is that his work is evocative of a broader cultural reality – Arabic culture, Egyptian culture but not something narrowly Arab or Pharaonic. He was greatly influenced by the [Hellenistic portraits found among the mummies of] Fayyoum.

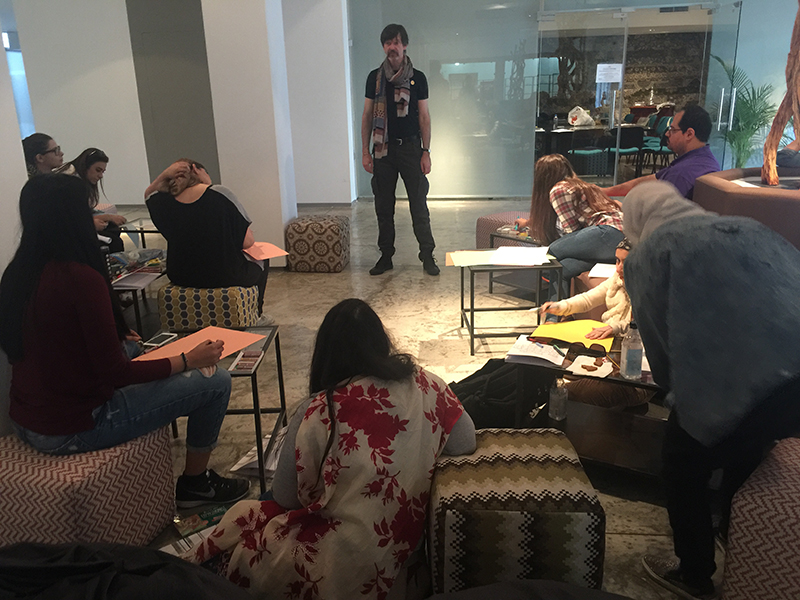

In addition to presenting her study of Tuni’s work, Taan conducted a three-day-long Tuni-inspired visual storytelling workshop. In his work Tuni has made repeated use of icons from Egypt’s multi-layered visual culture, copy/pasting them in different contexts, to absurd and sometimes surreal effect.

Workshop participants were encouraged to research the icons of their own visual culture, to decontextualize them, and erect narratives around them.

The first day of “The Copy/Paste Syndrome” was marked by a passionate talk by Lebanese fashion designer, LAU alumnus and Maison Rabih Kayrouz veteran Rayya Marcos. Framed as a lecture-performance – a form of address favoured by several Lebanese contemporary artists – Marcos’ talk discussed the creation of her award-winning Bird on a Wire collection.

Launched in 2009, Bird on a Wire debuted at the Starch boutique in Beirut’s Saifi Village. Later it went on show at Doha’s Katara Art Center. The collection came “home” in 2011, at “Starch Your Summer,” a collective exhibition at the Beirut Art Center.

In July 2014 Bird on a Wire won the Woolmark prize for Middle East and India for its revolutionary introduction of new pieces to the wardrobe and doing away with such conventional notions as the “shirt,” the “skirt” and the “dress.”

Also on hand at Nuqat 2015 was British-born conceptualist Jason Steel. He is credited with having “visioneered” a fashion education programme at LAU that explores “the meaning of clothing in an emerging fashion economy.” Integral to this programme are “menswear, unisex concepts, experimental fabrics, contour/stretch and tailoring as well as branding and entrepreneurship.”

In CUT, his talk at “The Copy/Paste Syndrome,” Steel discussed how to create a fashion design programme from scratch and the impact this could have on the wider creative community. The talk was premised on the importance of ensuring that, in emerging markets, the creative process work in tandem with commercial sensibilities, to prepare young graduates to fend for themselves in a relatively hostile environment.

Industrial Designer Raffi Tchakerian, a visiting professor at LAU’s Department of Fine Arts, is interested in role designers can play in the emerging entrepreneurial aerospace industry. Tchakerian is interested in the interactions among humans, their tools and technologies and the environments these were designed to manipulate. In 2012 he joined the Warka Water project, a water harvesting tower installed in southern Ethiopia in 2015.

He was invited to Nuqat to conduct a four-day workshop devoted to repurposing – or “remixing” — IKEA products. At the end of four days, Tchakerian’s collaborators had used the bits and pieces of Swedish-designed furniture to erect an “eco-friendly diwan.”

“For the past seven or eight or 10 years I’ve been in Italy to see if there’s potential for industrial design collaborations with local firms,” Tchakerian said. “I’ve been working with aerospace architects, applying technologies designed for extreme conditions — space, the surface Mars and so on — to improving conditions for humans living in harsh terrestrial environments.

“At the Nuqat conference we repurposed Ikea products to create a structure compatible with local culture. Personally I hate working with interior and lighting design … I’m interested in asking how innovative design ideas can improve people’s quality of life.

“Ikea provided me with the opportunity to take their products, rip them apart and try to build something that not only adds value but enhances well-being. The result — a diwaniyya, which has a strong local cultural imprint — looked nothing like the original product.”

Tchakerian says that there’s little trace of copy-paste syndrome in his line of work.

“It isn’t copy-pasting to take an existing product, repurpose and improve upon it. All our knowledge is based upon what came before.

“If an engineer says, ‘Design me a car’ or ‘Design me a house,’ ultimately you’ll wind up with something that looks more or less like a car or a house. It’s less important to build something completely different than it is to ask what you can do to provide a new experience for the user.”

As a case in point he cites Elon Musk, one of the first private sector designers to have access to outer space and the mind behind companies like SolarCity, Tesla Motors and SpaceX.

“There is a copy-past element to his design, yes, but there are two ways of copying. You can do like Chinese manufacturers, whose cheap knock-off products really are copy-paste jobs. Or you copy in a way that [improves upon the model].”

Indeed, terrestrial applications of aerospace technologies would seem to defy copy/paste approaches.

“Most of the technological innovation we have has emerged from one of two sources – the needs of the military or those of space exploration,” Tchakerian said. “Our solar panel technology, for instance, is based on innovations designed for space exploration.

“Developing technology for space exploration hinges on two principles: efficiency and in situ resource utilization.

“The water tower Waka built in southern Ethiopia collects moisture from the air. When designing it, we looked at what local traditions resources and technologies were available to draw upon.

“It so happens, for instance, that this region of Ethiopia is among the largest producers of bamboo. It’s also very hard to use trucks to transport materials to and from that region of the country. The humidity is such that we also noted a great deal of overnight water condensation. That condensation is a water source.

“All these factors came into use in designing the Waka water tower.”