Nature in Design

Nature is a generous and never-ending source of inspiration for designers. It is itself the most creative, diverse and mysterious of designers, explored by scientists seeking to mimic its processes and power, and artists seeking to reflect its beauty. Rarely, if ever, can nature be imitated to positive effect. And just as engineers inspired by birds did not try to build a plane using feathers, creative fashion designers do not simply craft skirts from grass or stitch flowers onto shirts.

“I draw inspiration from the curves, textures, volume, shape and colors in nature when designing my garments,” says final year student of fashion design Nour Daher. “Colors are a particularly strong fixture in my work, as they are all natural and found in nature,” adds the soon to be graduate, who eschews minimalism and prefers the bold and bulky prints of designers like Mary Katrantzou, at whose studio in London she interned last summer.

“As a child, I observed nature in its many forms,” says Daher, the daughter of an agricultural engineer. “And during my foundation year at LAU , our instructors encouraged us to sit outdoors while sketching.”

Just as natural spaces encourage inspiration and creativity in designers, so too do they in children. An appreciation for this relationship between nature and learning led to the development of a new course for LAU students of architecture and education. “Topics in Architecture: Spaces for Education” explores how outdoor spaces can be materialized so as to function as an effective learning tool for children, explains Assistant Professor of Architecture Roula el Khoury, who co-teaches the course with Garene Kaloustian, assistant professor at the Department of Education.

“Our students have been working together to rethink the outdoor space of the nursery at LAU ’s Beirut campus, which serves as a lab for students of education,” says el Khoury, who recently invited a horticulture specialist to give her students a guest talk about garden learning. “There are so many beneficial aspects to learning outdoors. Among other things, children develop a sense of texture and sound through this interaction with nature.”

Reem Hilal, a fifth year student of architecture attending the course, concurs. She is part of a multi-disciplinary group of students working on developing a proposal for a sensorial garden at the nursery. “Natural substances engage our senses far more than synthetics. Wood and plants not only have texture, but also make sounds, release odors and have color. They tickle all our senses at once, which is why our strongest childhood memories are more often related to environments with a lot of nature,” explains Hilal, whose group has decided to design a nursery with a lot of different plants. “Our surroundings shape us, so we must design them as a reflection of how we want to be shaped,” she points out.

Landscape architect Bachar el Amine, a part-time instructor at LAU , is likewise a strong proponent of ensuring that space is designed to imbue social development and cohesiveness. While nature, he says, refers to the natural setting, which can be factually and indisputably defined, landscape is the projection of an area of nature that is projected by the designer or in the mind of those perceiving a space.

“We don’t appreciate the impact of landscape enough in this region,” emphasizes el Amine. “The way we design our environment - our ground - is not limited to a garden. It impacts how we define, organize and see our territory.”

El Amine believes that the U.K. provides a positive example of how a country’s landscape should be reconstructed post-conflict. “They engaged the people in the development of a collective vision to redesign their environment and therefore their society,” he says, disappointed that Lebanon and other countries in the region do not nurture such collective efforts. “Being engaged in my landscape is fundamental to my sense of belonging in and to a space that is an extension of myself,” explains the Ph.D. candidate, who is researching the relationship between pan-Arabism and the physical environment.

Daher, the fashion student, is also intrigued by the impact of geography and nature on identity. “Different communities developed different styles of dress based on the geography and climate of the space they live in, and this becomes part of their visual culture,” she points out. As part of her research, Daher looked through old family albums to see how people from different areas and different times dressed, their choices were not only affected by space but also by war. The resulting collection, titled Relics, will be among those worn on the catwalk at a fashion show to be hosted this June by the School of Architecture and Design. The event will showcase the work of students of the first graduating class of the B.A. in Fashion Design in collaboration with ELIE SAAB and the London College of Fashion.

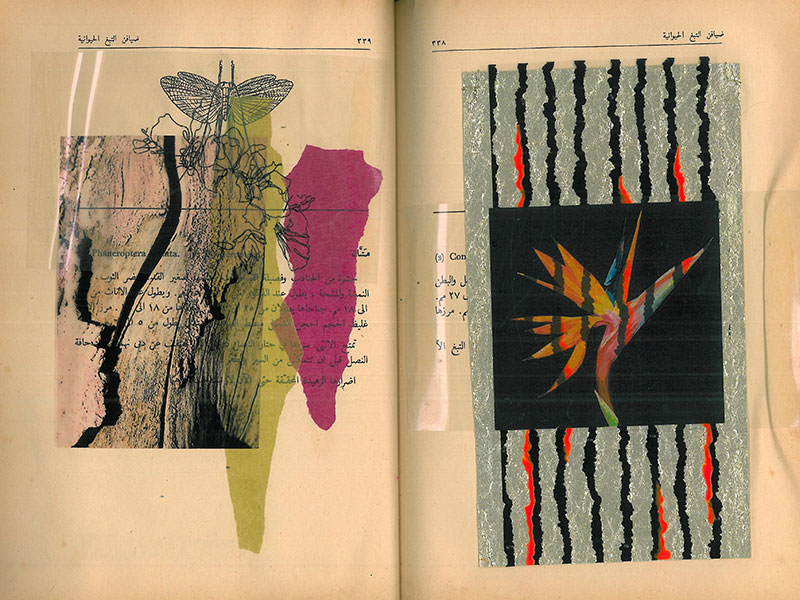

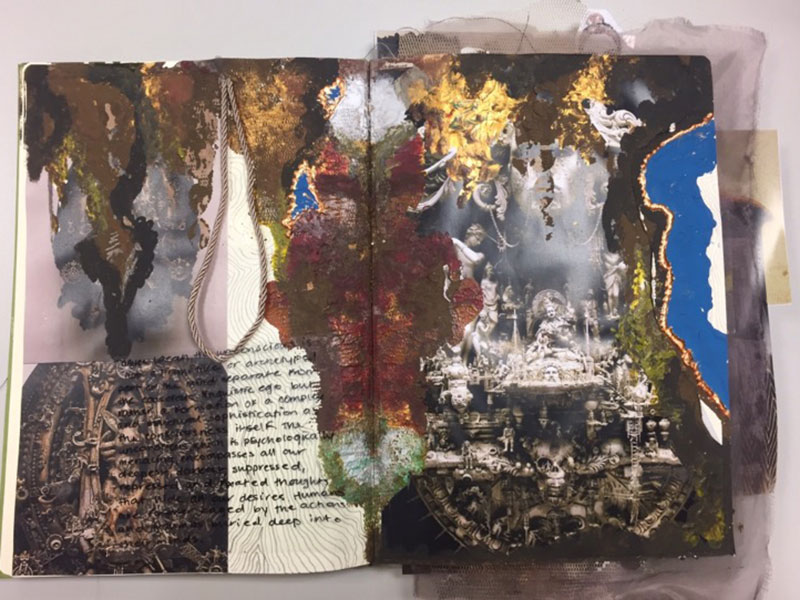

Among them is Christie Dawli, whose final year collection, named after the German word for “metamorphosis,” is inspired by the process of natural transformation. “My design was driven by a desire to deconstruct the unconscious,” says the designer, who holds a degree in psychology. “The process of reconstructing it thereafter led me to consider moths, which morph, and so I created a 3D printed fabric based on a microscopic image of their wings.”

One might consider war or skyscrapers when looking to portray destruction and construction, but nature, says Dawli, lets her creativity wander in a more organic way, which inevitably leads her to thoughts of nature and its creatures. “I find it less rigid and more breathable.”

Graphic designer Gokhan Numanoglu shares Dawli’s interest in animals. The assistant professor at the Department of Art & Design draws parallels between the instinctive way in which animals design and the way human beings approach design. “Birds make nests without being taught, ants build complex homes and bees make perfectly geometric honeycombs,” explains the designer by way of example.

Numanoglu is not sure whether human beings design through instinct or intuition, but he points out that while animals may design what they need to survive instinctively, they are directed by what is available to them in their environment. “Their restrictions influence their design. Similarly, we as designers need to limit ourselves by setting criteria, because while animals design to survive, we design to facilitate.”

Much of what we, as people, want to design and create is inspired by nature, as are the solutions we come up with. Scientists are now looking to plants as they try to develop a solar fuel, just as engineers drew from fish while designing faster and safer cars and from birds while designing aircrafts. Manmade designs can never mimic nature - for it is too complex for us to truly understand, let alone emulate - but its role as a fundamental and core source of inspiration and knowledge is likely to continue for millennia to come.